LOSING RAGE

nico mjones

DH

Introduction

This website is a research project.

Every day contemporary events are recorded. These events may be insignificant beyond the experience of them, or they may be significant in social, cultural, or political trends, or rendered important retroactively in historical study. Not all events are recorded or recorded the same way, and not all records are preserved indefinitely. This research is predicated on the questions of what is recorded, how are things recorded, and what and why records are preserved.Canada is well known for its decades-long struggles with binationalism, biculturalism, and bilingualism between Anglophones and Francophones, These questions still figure today, and complicate, in Canada amidst the rapid growth of discourse surrounding multiculturalism in a diversifying Canada. The discourse today however is significantly less heated than in the period of terrorist groups, martial law, and repeated independence referendums in the 1960s through 1990s. The Quiet Revolution, the October Crisis, the 1980 & 1995 Quebec independence referendums, and the Meech Lake Accords are the stand out events of the history of the most conflicted period of the relationship between Anglophones and Francophones since the founding of Canada. All of these events are highly documented and analyzed, contemporarily and in historical reflection. While these may be considered the pivotal moments of the issue, what may be missed are the smaller events that may not have been deemed particularly significantly either contemporarily or retrospectively. Analysis of these events and the state of their recording and preservation may provide an even greater depth of understanding than further analysis of the most renowned.One such case is a particularly controversial event around the Meech Lake Accords. It is a case of flag desecration, in either 1989 or 1990, in either Sault Sainte-Marie, Ontario or Brockville, Ontario. In “Beheading the Saint” by Genevieve Zubrzycki, the evolution of aesthetics in the Saint Jean Baptiste day celebrations in Quebec are examined in the context of the most traditional practices, the Quiet Revolution, and beyond. Zubrzycki details the 1990 Saint Jean Baptiste concert, including a performance by Diane Dufresne (Zubrzycki, 2016. pp.134-135). The lyrics are included, and there is a note appended to the line “Do not ever again wipe your feet on my flag” (Zubrzycki, 2016. p.135). The note reads “Dufresne refers to images of a crowd in Sault Sainte-Marie, Ontario wiping their feet on the Quebec flag during the intense negotiations at Meech Lake. The images were widely broadcast in Quebec” (Zubrzycki, 2016. p.135). Although Zubrzycki states that these had been shown in Quebec, and were popularly known enough for Dufresne to include in the song, finding the images or recording, or even confirming the event, is difficult. While Zubrzycki states it was in Sault Sainte-Marie, the confusion over the events will become clear in the exploration of it.The following will detail the searching for record and clarification of this event.

The First Search

As the goal is to find evidence of a proposed recent historical event, the most immediate action would be to utilize a search engine like google to find it. Since this is proposed to be a popularly known event, an academic search in a University Library may also be successful, but it isn’t necessarily the fastest or first action to occur in mind.Thus, the first attempt is a google search for “sault sainte-marie ontario quebec flag desecration”. On the first page, the first five results are relevant, the rest are not, and so these will be examined first.

Notably, the first four of these results are news articles from 1990 and 1991. While Zubrzycki does not give an exact date for the event, Dufresne’s performance was at the 1990 Saint Jean Baptiste day concert, which is held on June 24th. Thus, these dates would work for covering a relatively recent news event, although it would be impossible to be describing it immediately after the event if it is the one in Dufresne’s performance.

The Washington Post. (1990, November 25). LANGUAGES OPEN FISSURE IN ONTARIO SAULT STE. MARIE STUDIES ANTI-FRENCH REFERENDUM. Sun Sentinel. https://www.sun-sentinel.com/news/fl-xpm-1990-11-25-9002270409-story.html

The first article discusses a proposition on a referendum to emphasize the city’s opposition to French language rights, following the city having passed a law making its official language only English. What is most important is that there is no mention of flag desecration in Sault Sainte-Marie, instead, there is mention of “the powerful television image of militant Anglophones burning a Quebec flag in a highly publicized incident in Brockville, Ontario” (The Washington Post, 1990). This presents a complication, as the location is placed at the other end of Ontario and a different sort of desecration than stomping on the flag is stated.

Claiborne, W. (1990, November 23). SAULT STE. MARIE MAY HOLD ENGLISH-ONLY LANGUAGE VOTE. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1990/11/23/sault-ste-marie-may-hold-english-only-language-vote/3f7a7d19-ae63-467c-9aba-59fc1b4289a5/

The second result is in fact the same as the first, but on The Washington Post’s website with the actual author, where the former article had been republished by the Sun Sentinel with the author credited as The Washington Post. There is thus no new information in the article. There is the question of why the Sun Sentinel, advertising itself in its logo as a south Florida catering paper, would republic this news about Quebec and northern Ontario. For those that have lived in Florida, it is fairly known that Florida has a significant amount of Quebecois and other Francophone residents, and there are some relatively well known Francophone catering magazines that have been located in Florida, most having been published in the 90s as well. While diaspora may be the reason for this, it is outside the specific questions of this project.

Rowley, S. C. H. T. (1991, January 1). QUEBEC AROUSES ANTI-FRENCH BACKLASH. Chicagotribune.Com. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1991-01-01-9101010069-story.html

The third article, just a few months older than the last, covers much of the same issue. It provides a more in depth detailing of the Anglophone and Francophone conflicts in 1990 and 1991, including the support and opposition amongst Anglophones to Sault Sainte-Marie’s English law. There is again no mention of a flag desecration in Sault Sainte-Marie, but there is one of Brockville again, “A group of demonstrators burned and trampled the Quebec flag in Brockville, Ontario. That powerful image was played and replayed on Quebec news broadcasts, stirring up separatist sentiment” (Rowley, 2018). This description is closer to the one supposed in Dufresne’s performance and Zubrzycki’s analysis.

Talbot, D. (1991, March 3). Divided We Stand. Ryerson Review of Journalism :: The Ryerson School of Journalism. https://rrj.ca/divided-we-stand/

The fourth article provides even more in depth analysis of the issues surrounding Anglophone and Francophone conflicts in the light of the Meech Lake Accords. The event in Brockville is mentioned several times, particularly in the light of criticism of the media’s role in the negative events that had occurred, “As the debate gained momentum in the winter and spring of 1990, the coverage took on dangerous nuances. Images of intolerance littered our newspapers and polluted our television screens. Again and again, the media showed the spectacle of a handful of zealots in Brockville, Ontario, trampling the fleur-de-lis” (Talbot, 1991). Additionally, there is a somewhat enlightening passage with more details about the event,“The Quebec media in particular turned the debate into an emotional battle between French and English. What happened in Brockville actually occurred on September 6, 1989, long before Meech heated up. At the time, the image was reported around the world in newspapers such as Le Monde and The Guardian. Brockville made the news on television programs such as Telejournal, NBG’ Nightly News, Montreal Ce Soir and The National. It was discussed on radio current affairs shows like As it Happens and on the Montreal francophone station CKAC. But the Quebec media kept the image of bigotry alive until the demise of the Accord. Le Point, the French equivalent of The journal, replayed the incident in March 1990, six months after it made the news. The image remained vivid throughout the debate. The journal reported that out of 1,000 Quebecers, 60 percent thought the flag trampling occurred in March or April 1990. Brockville was referred to in emotional editorials calling the incident symbolic of Canada’s dislike for Quebec, and in angry letters to the editor in Le Devoir, La Presse and Le Soleil” (Talbot, 1991).This becomes the first solid clarification of the event of flag desecration. Firstly, an exact date is given, September 6, 1989. Secondly, the conflation of its date with a later point in 1990 is also useful for explaining why different sources might have different dates. Lastly, the explanation of Quebecois media’s exploitation of the event is very useful. This explanation of the conflations and media exploitation of the event may begin to explain why there is such a disconnect between the articles about the event and even the analysis by Zubrzycki. The article further mentions a 1990 documentary about the event produced by the CBC, several Quebecois journalists critically discussing the event and its portrayals, and a show of solidarity with Quebecois by Anglophones against the desecration that occurred in June of 1990 in Regina, Saskatchewan (Talbot, 1991).

Wikipedia contributors. (2005). Talk:Bilingual belt. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk%3ABilingual_belt

The final source from this set is a Wikipedia talk page for the Bilingual Belt in Canada. The discussion between contributors is about whether Sault Sainte-Marie falls within the Bilingual Belt, and one of the contributors has cited the previous detailed Ryerson article.Notably from this initial search, most information comes from the Ryerson article. It clarifies issues of misinformation and exploitation of the event in the media, gives an exact date, other potential sources, and is interestingly cited in a Wikipedia discussion on bilingualism in Canada. However, there are no images in any of the articles, there are no recordings either, and these appear to be largely Anglophone points of view of the events. Given that Dufresne is Quebecoise, it would then be important to explore the issue from Francophone points of view. And perhaps, as the event had been so displayed in Quebecois media, there may be more likely to be visual records there.

Second Search

Correcting for the location, the next effort would be a second google search, this time in French. Several phrases are used, such as “profanation au drapeau en brockville”, “outrage au drapeau en brockville”, “Profanation du drapeau du Québec brockville”, and “outrage au drapeau du Québec brockville”. Unfortunately, these results were very scattered and largely irrelevant. Some of the results included the previous results, such as the Ryerson article.

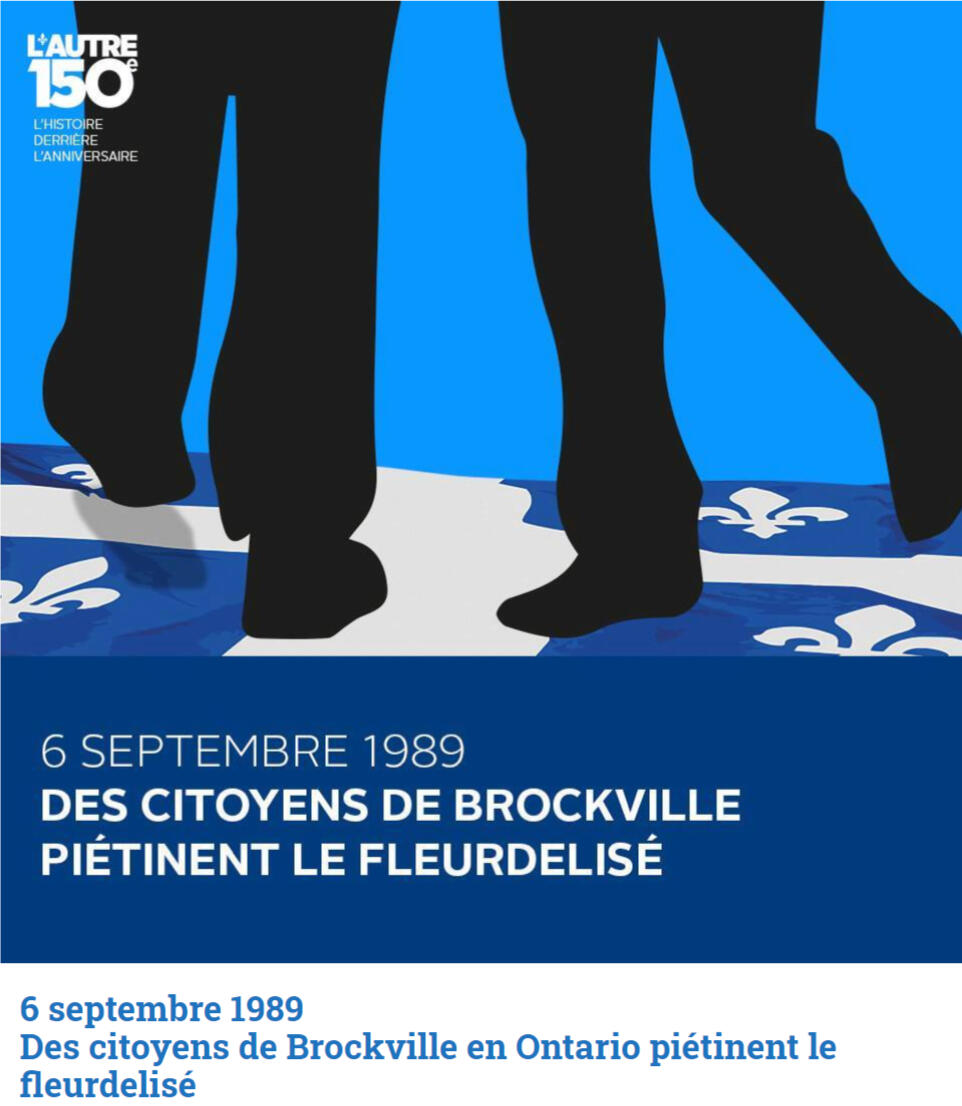

Des citoyens de Brockville en Ontario piétinent le fleurdelisé. (2019, September 6). L’agenda Indépendantiste. https://aqction.info/evenement/1989/2019-09-06/

On a website for a Quebec independence movement organization, this page discusses the event in Brockville and the legislation in Sault Sainte-Marie. It also displays a graphic depicting the event. This offers relatively little insight, although notably, the page does have the correct date and events.With little to go on with google, the next step would be to look at the Quebecois media which was mentioned to have covered the event in the Ryerson article. First are the media which were discussed when reflecting on the exploitation of the event by media.Firstly, the French newspaper Le Monde is stated to have displayed the image during its initial occurrence. Using Le Monde’s search, there are some articles about the Meech Lake Accords, reserved for paid subscribers, but none of these seem relevant, and there are no results when searching specifically for the flag or Brockville. Le Monde does not seem to have preserved any presence of the event in its accessible archives.Next, CBC-Radio Canada’s Telejournal is also mentioned in the Ryerson article. The search engine on the Telejournal page, however, also has no results for keywords such as “Brockville drapeau”, “Meech Lake”, and so on.Lastly, there is Le Point, another French paper, more like a tabloid. There are again, no results for search terms such as “Brockville” or “profanation drapeau Quebec.These searches having proved entirely unsuccessful may point to further evidence for the claims that they had portrayed the issue exploitatively, as shocking or hotly debated content that may draw in readership. There were others mentioned as well in the Ryerson article, but these were from journalists who discussed the exploitation and the event more accurately.First is Le Devoir, who’s search provides an abundance of results.

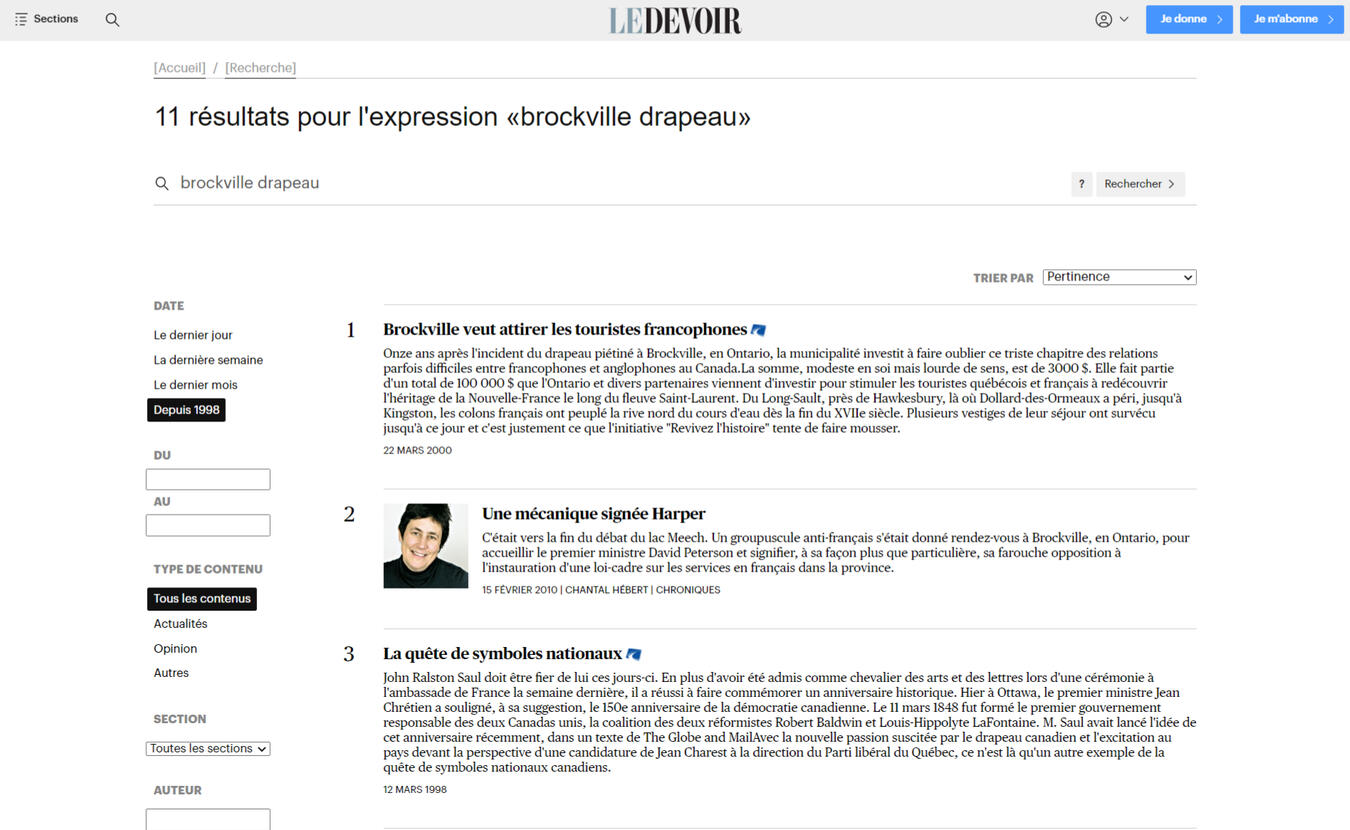

Le Devoir. (2020, December 12). Le Devoir. https://www.ledevoir.com/recherche?tri=pertinence§ionid=&expression=brockville+drapeau&triwidget=pertinence&triwidget=pertinence&date=depuis1998&format=tous§ion=&datedebut=&datefin=§ion=&collaborateur_nom=

The first result is not so much about the event, but about its history, starting with “Eleven years after the flag trampled incident in Brockville, Ontario, the municipality is investing in making people forget this sad chapter of the sometimes difficult relations between Francophones and Anglophones in Canada.The sum, modest in itself but heavy with meaning, is $ 3,000” (Le Devoir, 2000). The second article uses the event as a comparison to other events in Canada, noting that if Meech Lake Accords had not failed the Brockville event may not have been of the significance that it was (Hebert, 2010). The last article of relevance discusses reconciliation with Francophones in Ontario over issues like the official monolingualism law of Sault Sainte-Marie and the Brockville incident (Orfali, 2015). It does, however, at the end of the article, include a link to a PDF produced by Le Devoir displaying headlines from the time of the Meech Lake Accords and Sault Sainte-Marie passing its monolingualism law, however, none of these include images of the Brockville incident, only an image of a related anti-French protest in Thunder Bay.The second paper of these papers listed in the Ryerson article, La Presse, has nothing more than a passing mention of the Brockville incident in the results.These results provide some Francophone views, though quite limitedly. While Le Devoir had several articles giving quite in depth discussion of the event and its surrounding context, the other sources had little to nothing on the event. Le Devoir also provided some images of the headlines and a related protest in Thunder Bay, but still no images of the Brockville flag desecration.Searching for visual evidence of the event required a disparate search across several platforms. Google’s Image search, the CBC’s archives, Radio Canada’s Archives, several searches for the CBC-Radio Canada documentary on the flag burning, and utilization of Carleton University Library’s database search. None of these but the Carleton University Library database produced any further results whatsoever, and it did not produce any results with images. One source did clarify that the visuals shown on TV and newspapers were of the trampling, however, some journalists recorded afterwards, the Quebec flag was spit on and subsequently burnt (Ward, 1990). This helps to understand the earlier issue in why there were different claims of trampling and burning.

Contact

Thus far the search proved unable to find visual evidence of the Brockville flag desecration. There are however potential issues in this search, as the French may be inaccurate, there may be articles or other sources which do have the picture in other databases, or there may be physical archives with the images or videos.There is a historical archive in Brockville, however, it is not operating public access to the archives during the currently occurring Covid-19 pandemic. Local news stations may also have archives that may include their video. It may also be possible to utilize contact information of the various journalists and academics who had written on the subject for advice on where to find out more as well. These are all potential explorations.Fortuitously, a Quebecois contact was able to provide assistance, providing a more common terminology regarding the event, “piétiner le drapeau du Québec 1989”, as well as a link to a Radio Canada interactive archive on the life of Brian Mulroney displaying an image of the desecration from Canadian government archives.

Chronologie de sa vie. (n.d.). Radio Canada. http://s.radio-canada.ca/sujet/brian-mulroney/_complements/chronologie/timeline2/index.html

While the first effort to find the image had failed, support from a Quebecois peer in terminology and locations proved to be the key to finding it. Notably, the images of it were still incredibly rare even still. The only other significant result was a website discussing anti-French racism.

Impératif français | Racisme et francophobie. (2017, September 7). Imperatif Francais. https://www.imperatif-francais.org/articles-imperatif-francais/articles-2017/racisme-et-francophobie-2/

Contacts are important in research, as strongly evidenced by the success only found when reaching out to a peer.

Analysis

While difficult, the research for this event was eventually successful. The initial searching did not prove fruitful for the images, but it did provide a great deal of contextualization and analysis that helps to understand the event more. With the image, the discourse of the articles, and the process of itself, there is a great deal to be understood about the event, its role in Canadian history, and the potential reasoning behind how it has been recorded and preserved.Zubrzycki’s book is primarily focused on the aesthetic changes of the Saint Jean-Baptiste day celebrations, and uses this to analyze some more recent events in Quebec’s history, such as the Meech Lake Accords and religious symbols laws. Although the mention of the flag desecration event is small, and it’s irrelevancy to many of the larger points may explain the error in location claimed, there is value in considering Zubrzycki’s theory in the study of the Saint Jean-Baptiste celebrations in application to the Brockville flag desecration event.The Quebec flag desecration in Brockville seems to have evolved in its meaningfulness with time. When first occurring, it made international news amidst the controversies of the Meech Lake Accords. It seems that, as the Meech Lake Accords collapsed, media in Quebec and Quebecois’ concerns lead to an even greater politicization of the event. Although the event had occurred in September of 1989, it was reinvigorated in the repeated portrayals in the media later starting in March of 1990, just three months before the end of the Meech Lake Accords, auspiciously the day before Saint Jean-Baptiste day. It becomes evident just how significant the Brockville flag desecration would have been in the contemporary narratives of the time during these developments, and thus its reference in Dufresne’s performance would have likely been very popularly recognized amongst the Saint Jean-Baptiste day concert goers.The Brockville flag desecration continues to be remembered by Francophones in Canada, as articles and websites reflect upon it over the years since. The event carries much of the original tone used during its height of awareness, featured in articles about anti Francophone racism and reconciliation for Francophones in Ontario. It has remained more important amongst Francophones and has continued to carry concern over the status and treatment of Francophones.The question of its limited presence on the internet, and effective non existence in the English internet is difficult to answer. It may reside more with the French speaking internet due to the greater concern carried with it and fear of mistreatment. It may also be less present on the English speaking internet out of the awareness of manipulation, or the feeling of guilt. Analysis of media exploitation of the event seems to be almost entirely in the English internet, which may help to reduce the importance of maintaining awareness of the event due to the sense of it having been overblown. Conversely, the Anglophone counterprotests to the desecration that occurred contemporarily, as well as the efforts to reconcile the issue, including with provincial funding, may indicate a desire to erase the issue from history.

Critical Methodology

The methodology of this research was both planned and organic. The intention was to capture how one would research a controversial topic with little academic analysis utilizing digital methods. The structure and results of the research provide information to analyze itself.With a topic that has less academic coverage, original research is necessary to proceed in analysis of it. For a newsmaking event, the potential of this research can heavily depend on the record keeping of events. While it may be expected that news agencies and related organizations would maintain strict recordkeeping, they often do not, especially if the pressures of profit incentives are the focus over recordkeeping. Additionally, records kept may not be made publicly available or public facing, either due to financial concerns or perceived lack of interest. Thus, the information may be available, but difficult to find without the proper connections or procedures, or even the awareness of them.Notably, many sources stated to have covered the event did not retain any accessible information about it. Examples such as The Guardian and Le Monde were said to have covered the event at the time, but their websites did not contain any information. The Guardian in particular has had an emphasis on recordkeeping, and so particularly stands out in lacking the coverage. The lack of access through CBC-Radio Canada is also noteworthy. The Brian Mulroney Radio Canada interactive archive was not found through Radio Canada’s website but through a reverse image search of the image. It is also merely one image out of dozens, but the seeming lack of access to this content presents another consideration for where content exists but is not accessible.While the image was found, no video was. The video may perhaps exist in the same place as the image originally comes from, the Library and Archives of Canada’s Archives of Brian Mulroney. The local history center in Brockville, or the local news sources, may also have archives of the video, however, the general politicization and local government efforts to move beyond the issue may also bleed into record keeping, and thus prevent its presence there.It would seem odd that something deemed so important as to have been consistently displayed in the news for some time would become so difficult to find. The politicization may help explain it, but it may also be a question of utility. As most sources emphasize, the Quebecois people are well aware of the imagery and its history, and it holds most the importance for them, with even the people involved in destroying the flag having stated they were unaware of the power of the images. The conflicts between Anglophones and Francophones in Canada have become much less heated, and although issues still arise, clearly do not have the same power, as kidnappings or terrorists being involved in the problems would be unheard of today, but quite recent at the time for the 1989 event. It thus may be that the event has lost social utility, with the Quebecois of the time aware of it in memory, but there being little need to maintain the preservation of it in the contemporary sociopolitical setting.While there may be many potential reasons, the event’s lack of accessible visual representation raises further considerations. Does the politicization of events help or hinder their preservation in records? Is the potential loss of records of an event acceptable? Can this loss be “natural” in the sense of its record losing importance or use? The creation, maintenance, and loss of records has become of even greater importance and discussion with the development of the internet and digital technologies, which both help to maintain records, while also coming with certain increased risks in loss. As evidenced in this research, the internet and digital technologies, such as the public facing archives of news sources, were often not of use, while others were able to help secure research goals.

Citations

Chronologie de sa vie. (0000). Radio Canada. http://s.radio-canada.ca/sujet/brian-mulroney/complements/chronologie/timeline2/index.htmlClaiborne, W. (1990, November 23). SAULT STE. MARIE MAY HOLD ENGLISH-ONLY LANGUAGE VOTE. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1990/11/23/sault-ste-marie-may-hold-english-only-language-vote/3f7a7d19-ae63-467c-9aba-59fc1b4289a5/Des citoyens de Brockville en Ontario piétinent le fleurdelisé. (2019, September 6). L’agenda Indépendantiste. https://aqction.info/evenement/1989/2019-09-06/Hébert, C. (2010, February 15). Une mécanique signée Harper. Le Devoir. https://www.ledevoir.com/opinion/chroniques/283134/une-mecanique-signee-harperImpératif français | Racisme et francophobie. (2017, September 7). Imperatif Francais. https://www.imperatif-francais.org/articles-imperatif-francais/articles-2017/racisme-et-francophobie-2/Le Devoir. (2020, December 12). Le Devoir. https://www.ledevoir.com/recherche?tri=pertinence§ionid=&expression=brockville+drapeau&triwidget=pertinence&triwidget=pertinence&date=depuis1998&format=tous§ion=&datedebut=&datefin=§ion=&collaborateurnom=Orfali, P. (2017, February 24). L’heure est à la réconciliation avec les francophones de l’Ontario. Le Devoir. https://www.ledevoir.com/politique/canada/451040/sault-sainte-marie-25-ans-plus-tard-l-heure-est-a-la-reconciliation-avec-les-francophones-de-l-ontarioRowley, S. C. H. T. (2018, September 2). QUEBEC AROUSES ANTI-FRENCH BACKLASH. Chicagotribune.Com. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1991-01-01-9101010069-story.htmlTalbot, D. (2014, October 1). Divided We Stand. Ryerson Review of Journalism :: The Ryerson School of Journalism. https://rrj.ca/divided-we-stand/The Washington Post. (1990, November 25). LANGUAGES OPEN FISSURE IN ONTARIO SAULT STE. MARIE STUDIES ANTI-FRENCH REFERENDUM. Sun Sentinel. https://www.sun-sentinel.com/news/fl-xpm-1990-11-25-9002270409-story.htmlWikipedia contributors. (2005). Talk:Bilingual belt. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk%3ABilingual_beltZubrzycki, G. (2016). Beheading the Saint: Nationalism, Religion, and Secularism in Quebec. University of Chicago Press.